Firing his rifle, he pierced the man in the heel. It was the only part of the Shawnee's body that was visible from behind the tree. The Indian, crawled away the best he could to return to his fellow braves. Samuel Gwinn fired this shot according to his grandson, Andrew Gwinn, at the Battle of Point Pleasant. Samuel had gone to Point Pleasant with about 1,200 other militia from Virginia, to force Chief Cornstalk and the Shawnee's out of West Virginia and Kentucky. The results of the fighting were favorable to the Virginian's and their commander Col. Andrew Lewis. After a battle that lasted from dawn to dusk, the Virginians held their ground. The Shawnee's retreated to Ohio and were shortly there after "convinced" to sign a treaty with Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, agreeing to concede the lands south of the Ohio River. The Battle of Point Pleasant was only one of the military engagements Samuel Gwinn experienced during his ninety-four years.

|

| Battle of Point Pleasant, WV Source: http://cavenderia.blogspot.com/2010_05_01_archive.html |

|

| Statue of Andrew Lewis on the Battle of Point Pleasant monument. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Andrew_Lewis.JPG |

Samuel was one of five sons, a middle child, of Robert Gwinn and Jane Kincaid. He grew up on the 544 acre farm of his parents, traversing both sides of the Calf Pasture River. Samuel was the first of our direct line of Gwinn's to be born in Virginia. His father was the immigrant to the Virginia Colony settling his family on the western frontier. While the eastern plains of Virginia had been settled for more than one hundred years, the valleys beyond the Blue Ridge were without the comforts of society. Imagine a life where one relies only on family, neighbors, and a rifle to survive. This was the truth for our first family of Gwinn's.

Samuel grew to adulthood among the fertile valley between the Allegheny and Blue Ridge Mountains in Augusta County. The land provided for the needs of the family; a flowing river, cool springs, and mountains teeming with game like deer, elk, and bear. Religious needs were met at the Rocky Springs Presbyterian Church. Most of the settlers of this area were of similar heritage and religious beliefs. Even family legend suggests the Gwinn's and Graham's traveled from Ireland together to come to America. We certainly know they were next door neighbors on the Calf Pasture River with property adjoining one another. For my first cousins, here is an interesting note. Robert Gwinn is our 6th Great Grandfather in a direct line to our Grandfather, Lemuel O. Gwinn. Robert Gwinn's neighbor on the Calf Pasture, John Graham Sr., is also our 6th Great Grandfather, in a direct line to our Grandmother, Annie Stickler Gwinn. It was through John Graham's daughter, Ann, who married John Kincaid that this line descends to our generation.

While the Calf Pasture may sound like a paradise with it's great wealth of natural bounty, it was not an easy life on the western frontier of the Virginia Colony. These settlers endured hardships as well. The wild game that provided meat and pelts also threatened livestock. Foxes, wolves, and even panthers could attack farm animals or even people. Harsh winters, drought, storms, and disease would have been constant battles for survival. The worst fear however, was probably the Natives, who could quickly put an end to tranquility and peace in the region. The French and Indian Wars (1754-1758) would have been fought when Samuel was a child. His father, Robert, had served in this war. The French had encouraged the Natives to attack settlers along the frontier. Although the Calf Pasture area was not in immediate danger, Robert must have been compelled to serve his neighbors to the west. There were attacks in Augusta County along the Cow Pasture and Jackson Rivers where hundreds of men, women, and children were killed by raiding Native Americans. The Shawnee in particular were not welcoming of the European expansion into their hunting grounds of Western Virginia.

Samuel's early years most likely consisted of household chores, farming, and learning to hunt. Gatherings of family and neighbors on occasions of religious services like weddings and funerals would have also been part of the social life. Samuel had his first child at the age of about fifteen years. His name was Moses Gwinn, our 4th Great Grandfather. Many who do research on the life of this family are contentious about the birth year of Samuel Gwinn. Most would agree it was between 1745 and 1752. I believe the earliest date. Here's why. Samuel's tombstone says "Sacred to the Memory of Samuel Gwinn who died on March 25th 1839 in the 94th year of his Age." This would confirm the 1745 birth year.

Another reason his birth must have been the earlier of these dates is due to his son, Moses. By all accounts, Moses was his oldest son, mentioned in early records and even in Samuel's will. Moses died December 28th 1822 in his 62nd year. This means he was born in 1760. Samuel could not have been born in 1751 and produced a son in 1760. Those who disagree say the tombstones are both wrong. They point to the military pension file of Samuel Gwinn where he states he was 23 in 1774. This proves a birth year of 1751. If the pension file is to be correct, there is another problem. Samuel also states in this same document he came to Monroe County, present day West Virginia a year or two after 1774 (about 1776) with his two children and wife. His wife was Elizabeth Graham nee Lockridge. She was a widow with two children when she married Samuel Gwinn. They were married sometime between March 1774 when her first husband, Robert Graham, died and June of 1775 when she gives her daughters to Andrew Lockridge's care. She did not bring her daughters to their marriage, instead leaving them with her father who signed a bond for their security. She went with Samuel Gwinn and his two children to western Virginia. It is very unlikely they were able to produce two children in the time between their marriage and departing for the wilds of western Virginia. With this in mind, the family lore helps fill in the blanks. Samuel was married first to Elizabeth Speece. While there are no records to prove this, in my opinion, there must have been an earlier marriage for Samuel. We do know he married Elizabeth Graham when he was about thirty-years old and had many more children.A new wife and a new location....that must have been Samuel's plan. He was well suited for a journey into the western lands of Virginia. He had experience in the militia when he was drafted in 1771 to serve at Warwick Fort (Clover Lick) in Greenbrier County (present day Pocahontas County, WV) He served and was discharged under Captain Andrew Lockridge after three months service. Samuel reported only minor skirmishes with the Indians at this location. As previously mentioned, Samuel had enlisted in the militia a few months before the Battle of Point Pleasant. The meeting place before their month long march was at Camp Union, Lewisburg, WV. From there, the Augusta County militia traveled with Captain Charles Lewis, a brother of Andrew Lewis, from Camp Union to Point Pleasant. They were the first to leave Lewisburg with other units of soldiers to follow. Their march took them directly through Green Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. Little did he know, sixty-five years later, he would be buried above the road where he marched in Green Sulphur.

|

| Historical Marker at Green Sulphur Springs, WV near the present store off the I64 exit. |

There were two fronts in fighting the American Revolution, the British in the East and the Native Americans in the West. Many native tribes were again encouraged to kill the frontiersman, similar to how the French had persuaded Native Americans during the French and Indian War. In addition, the British had made alliances with both the Shawnee and Mingo tribes paying them for dead frontiersman. Samuel's service in the Revolution would be in the West. Carrying their limited belongings Samuel, his two children and new bride, Elizabeth, made there way across Augusta County into the area known as Lowell, Greenbrier County. (today it is Summers County, WV). More likely than war, Samuel's decision to go westward was probably due to family connections. He traveled not only with his wife and children, but also with his brother James Gwinn. The Graham's may have traveled with him or come a few years before him to this area of West Virginia. In fact, Samuel's first log home would be just across the Greenbrier River from Col James Graham's two story home and fort.

Life in 18th century near Lowell was perilous. Shortly after Samuel brought his young family to their new home, he was called out on duty to help in the protection against Indian raids. In 1776, he reported spending five months at Arbuckle's Fort, about 12 miles north of his home. Arbuckle's Fort was located where the Muddy Creek meets the Mill Creek. Just a year later he was at Thompson's fort for another five months. I'm not certain if he always took his family with him to the forts, but we know in some cases he did. In his own words Samuel said "All the people of the settlement took their families to the forts in the summer months where we lived pretty much in common. We would turn out all in a body and work each others corn and potato patches by turns. Whilst we would be working some one or two would be watching for Indians. We worked and watched by turns. We selected from among ourselves some one in whom we had confidence as a sort of leader or Captain- and in this way we got along as well as we could." At other times, the families would be at their own cabins. They would only go to the fort if there was a call that the Indians were about. There are numerous cases of reports of Indians. Some families spent only a few days at the fort, while others may have spent months there depending on the threat and the decision of the family. We know of one specific decision, by the Graham family, that proved to deadly.

|

| Created by Google Maps and labeled by Daniel Gwinn |

|

| Arbuckle's Fort 3 miles north of Alderson, estimated on archaeological research. (Built about 1774.) |

James Graham and his wife Florence lived just across the Greenbrier River from Samuel Gwinn's land. There home was of similar construction, but larger with dimensions of 24" by 30'. Today, there is a pedestrian bridge that still links these two properties. In the late summer of 1777, word spread through the community that the Indians were once again in the area, forcing the whole community to go to the fort. "After being in the fort for a short time, possibly two or three days, and no further signs of Indians having been seen or reported, James Graham, hoping the alarm to have been ill-founded, proposed to those in the fort that, if some of the men would go and stay with him a night, he and his family would go over home. Accordingly, they did so, some of the men in the fort volunteering to go with him. Shortly after he went home, either the same night or later, his house was attacked by the Indians." The following account of the attack was made by David Graham in 1899.

|

| Col James and Florence Graham House, Photo by Jack Whitaker. |

|

| The Graham House, Photo by |

"The assault was made in the after part of the night before daybreak. Not feeling well, Graham had luckily lain down on a bench against the door with his clothes on. The Indians made the assault by trying to force the door open, which they partly succeeded in doing. Thus aroused, Graham and his men placed the heavy bench and a tub of water against the door, and in this way prevented the Indians from gaining an entrance. A man named McDonald (or Caldwell), who was assisting in placing the tub against the door, while reaching above the door for a gun was shot and killed, the ball passing through the door. Thwarted in their effort in affecting an entrance into the house, the Indians next turned their villainous assault upon an outhouse or kitchen standing near the main dwelling. in this outbuilding slept a young negro man and two of the Graham children. The negro, whose name was Sharp, tried to escape by climbing up the chimney (chimneys in those days were large and roomy), but when discovered was ruthlessly hauled down from his hiding place, tomahawked and scalped. As this tragedy was being enacted, the cries of the two children who were sleeping on the loft above next directed the attention of the Indians to that quarter. They shot up through the floor and wounded the eldest of the two, a boy named John in the knee, then dragged him and his sister down and out into the yard. Finding that John was wounded so badly that he could not stand upon his feet and that he would be a burdensome prisoner, they at once dispatched him with a tomahawk and carried off his bleeding scalp as a trophy of their crime.

While this bloody scene was going on in the kitchen, Colonel Graham had gone upstairs and was shooting through a porthole at the Indians in the yard as best he could. The men in the lower part of the house loaded the guns and handed them up to him and he did the shooting. About the time they were trying to make the wounded boy stand up, several of them huddled together and fired at the bulk; when they suddenly dispersed. It is believed that one or more of the Indians were killed or wounded."

The video below tells the story as well as a short tour including a ghost story.

This attack must have severely shaken the community. Reports went out to other forts in the area. September 11th and 12th record requests for additional help against the Indians at Muddy Creek. In one of the letters, it states, people are "flying to Camp Union" (Lewisburg) for protection. Was Samuel and his family one of them? We do not know. But, he most likely was held up at Van Bibber's fort for at least part of the time. This fort was just 300 yards away from the Graham House. It was also known as Fort Greenbrier. Samuel certainly knew what it was like to have a plow in one hand and a rifle slung over his back. He must have always been watching over his shoulder. This new land promised great wealth and freedom, but it was not without a cost.

The winter months however, seemed to remain a relative time of tranquility. The Shawnee rarely made raids against the settlers in these cold and snowy months. Samuel said "I returned to my cabin and devoted the winter to hunting." I'm not certain how long Samuel and his family had to live this way, back and forth between forts and the cabin, but we do know he was stationed at Thompson's fort in 1778 when word reached the militia that Fort Donnally, just north of Lewisburg was under attack. The attack at Fort Donnally was one of the largest scale attacks by the Shawnee on any fort in the area.

You can read the details of this attack by clicking the link below. Samuel was certainly one of the sixty -six men who arrived at 4 P.M. to offer assistance. He was at Fort Donnally for five days.

Attack on Fort Donnally

The winter months however, seemed to remain a relative time of tranquility. The Shawnee rarely made raids against the settlers in these cold and snowy months. Samuel said "I returned to my cabin and devoted the winter to hunting." I'm not certain how long Samuel and his family had to live this way, back and forth between forts and the cabin, but we do know he was stationed at Thompson's fort in 1778 when word reached the militia that Fort Donnally, just north of Lewisburg was under attack. The attack at Fort Donnally was one of the largest scale attacks by the Shawnee on any fort in the area.

|

| http://www.wvgenweb.org/greenbrier/history/donnally.html |

|

| http://www.wvgenweb.org/greenbrier/history/donnally.html |

You can read the details of this attack by clicking the link below. Samuel was certainly one of the sixty -six men who arrived at 4 P.M. to offer assistance. He was at Fort Donnally for five days.

Attack on Fort Donnally

Under these severe conditions, Samuel and Elizabeth Gwinn's family grew in size to nine children. All of their children being born at the Lowell, Summers County home. Samuel increased the size of his land holdings while living at Lowell from about 400 acres to 1,000. On July 31, 1779, he added 245 acres along with 400 acres in 1784. More land followed in 1789 and again in 1798, all being adjacent to his original property. Hired hands and certainly slaves helped farm his land. Although the frontiers of western Virginia were not known for large slave populations, Samuel owned at least nine slaves, which is more than the average plantation of Virginia, where most slave owners had less than five. Samuel's grandson, Andrew Gwinn, said there were often as many as forty people working the plantation. Tobacco was most likely the cash crop that brought Samuel wealth and land. He certainly could have also grown wheat, oats, flax, and corn to supplement the family income. Tobacco was the main cash crop throughout Virginia, but towards the end of the 18th century, farmers were turning to harvesting grains that were also in high demand. Since Samuel was using forty people to help farm, it was most likely tobacco. Crops of grain did not require that many workers.

|

| Source: http://www.history.org/almanack/life/trades/traderural.cfm |

Elizabeth Gwinn and the children certainly would have tended vegetable and herb gardens including beans, carrots, cabbage, peas, parsley, rosemary, and lavender. She also probably spent a good deal of time spinning and weaving in the winter and spring, sewing linen made from flax to create clothing and bedding for her large family. Everyone in the family most likely helped with pigs, sheep, and the chickens. Oxen and horses may have been needed to help cart the tobacco and plow the fields. The life of a farmer and family would have been filled with hard work, but Samuel's increased land and wealth must have made them feel successful.

At some point, Samuel Gwinn started purchasing land at Green Sulphur Springs, certainly between 1799 and 1821 he had acquired four different tracts of land. Why he chose to move from his plantation is uncertain. He would have been about 55 years old and starting all over again. He had children ranging in age from Moses at 40 years old, to a new born baby, Ephraim, who came in January. Maybe his goal was to help provide for his sons. Moses and Samuel did not travel to the new property. Moses was most likely on his own and Samuel stayed behind and occupied the farm that Samuel Sr. was leaving. After the purchase of his Green Sulphur property, he took a couple slaves with him and cleared the land. He left his family at Lowell until this work was complete. After he had a home built, he brought his wife and children on horseback to the new home, Elizabeth carrying the baby Ephraim on the journey. The other children that came along were probably, Ruth, 17 years old, Andrew, 12, John, 11, Jane, 10, Betsy, 9, and Isabella, 7 years old.

Samuel Gwinn's new property might have promised him wealth in ways other than farming. At Lick Creek, which was a part of his land, was a salt lick, where deer and other wild game including buffalo would lick the ground at a low soggy place. In 1818, drilling was done in order to find salt. Using materials from the Gwinn farm along with others brought by a Mr. Shrewsberry, a well was dug down to sixty-five feet. To their surprise, Sulphur water was found instead of salt. The area became known as Green Sulphur Springs after this date.

|

| Green Sulphur Springs Store off of I64. Photo Credit: http://www.wvexp.com/images/thumb/6/60/Green_Sulphur_Springs,_West_Virginia.JPG |

Eventually, Samuel began giving his land to his children. In October of 1807, he gave his son, Samuel Jr. half of his old survey at Lowell, seven years later, he gave the other half to his son, Andrew. Eventually, Samuel Jr. would buy out his brothers half. The story goes, according to David Graham, who personally knew Samuel Gwinn, that Samuel wanted to divide up $12,000 in silver among his sons. David Graham remembers seeing Samuel Jr. and Andrew carrying their part of the silver by his father's house in common grain bags. They carried their silver over Keeney's Knob to their home near Lowell. Mr. Graham thought it quite strange since it was an "open secret" that Samuel Gwinn had his money laid up in his house and also common knowledge that his sons were invited on a certain day to receive each his share. These sons would carry their silver over fifteen miles back to their homes over public highways, mountains, and small communities and not worry about theft, but this was how it happened.

|

| Photo Source: http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/res/Education_in_BLM/Learning_Landscapes/ For_Kids/History_Mystery/hm5/the_pony_express_reride.html |

Another story concerning Samuel's wealth and wit also comes from David Graham. He said Samuel was in Lewisburg attending to business when a group of gamblers "induced him to play cards." They apparently knew Samuel had plenty of money. They allowed him to win the first few hands of cards, then offered to double the bets. Samuel told him about a lesson his mother had taught him. "It is a wise man who knew when to quit." So off he went with his winnings and "bade the gamblers good day."

|

| Photo Source: http://pokerfuse.com/features/comment-analysis/ dojs-response-campos-and-elie-summary-and-analysis/ |

In December of 1822, Samuel Gwinn would mourn the loss of his first born son, Moses. He was buried in the family cemetery at Green Sulphur Springs. Ten years later, his wife Elizabeth would also depart this life and be placed in the same burial grounds. Samuel would live on for seven more years, cared for by his children. Samuel Gwinn died March 25, 1839. He left a will which he had created a few months after Elizabeth's death, sharing his wealth with his children and grandchildren.

The Will of Samuel Gwinn

To wit--- Three Thousand and Fourteen Dollars in Cash to be entrusted in the care and management of my sons Samuel, Andrew and Ephraim- and laid out in Congress Land in the western County at Congress prices for the exclusive use and benefit of my Grandsons the sons of Moses, Samuel, Andrew, John, and Ephraim to be equally divided (or the value thereof) between each of them.

Next to my Grandson Samuel (Son of Samuel Gwinn) I give a Negro Boy name Tecumsey.

To my Grandson Samuel (Son of Moses) a Negro Boy named Hiram.

To my Grandson Samuel (Son of Andrew) a Negro Boy named Jingo.

To my Grandson Samuel (Son of John) a Negro Boy named David.

To my Grandson Samuel (Son of Ephraim) a Negro Boy named Liews aged about twelve years.

To my Daughter Ruth Jarrett a Negro Girl named Lisey Ann.

To my Grandson Samuel Jarrett a Negro Boy named Norris.

To my Daughter Isabelle Busby a Negro Boy named Grisby

To my Daughter Betsy Newsome a Negro Boy named Lewis aged about ten years.

And all my other Property not mentioned in the above bequests I wish at my decease to be equally divided between all my Children, To wit, Samuel, Andrew, John, Ephraim, Ruth, Jane, Betsy, Isabella, and the children of my oldest son, Moses Gwinn Dec'd, Together and share. The above I acknowledge to be my voluntary act and deed, subject however to any alterations which I may hereafter wish to make given under my hand and seal this fourth day of June 1832.

|

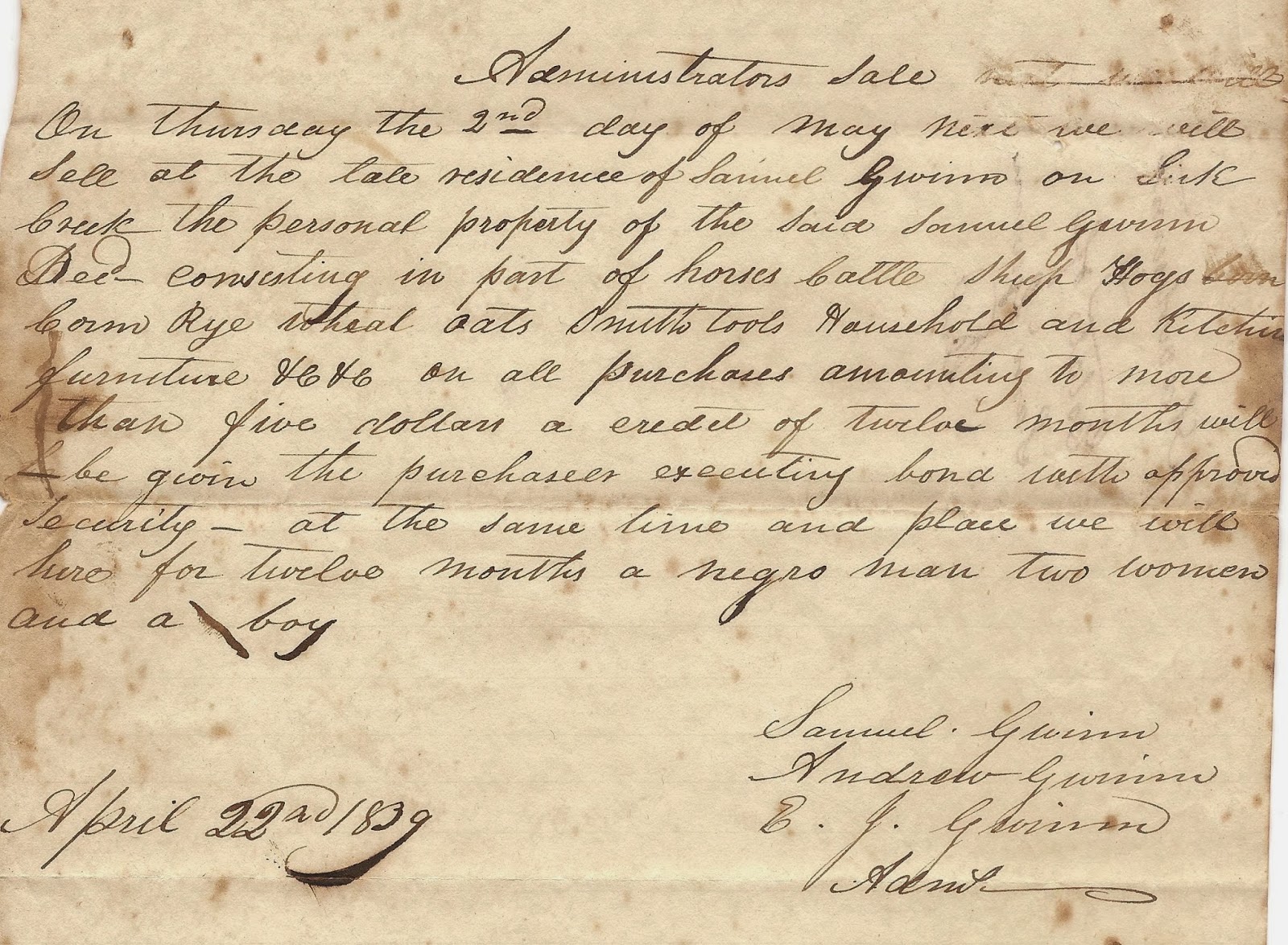

| Estate Letter for Samuel Gwinn given to me by Campbell Gwinn, a descendant of Ephraim Gwinn, when Dale Miller and I visited him at his home. |

Samuel rests along side his wife at the Wade Hampton Gwinn Cemetery on his Green Sulphur farm. Quite a few years ago, Dad, Mom, Scott and I visited the cemetery to pay our respects. Thankfully, the farm and cemetery is still in the Gwinn Family, owned by the descendants of Ephraim Gwinn.

|

| Bobby and Dan Gwinn at Samuel Gwinn's tombstone. |

|

| Samuel Gwinn tombstone. |

No comments:

Post a Comment